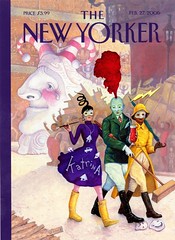

KATRINARITA GRAS

by

William Joyce

My wife was going to a 12th night party dressed as Hurricane Katrina. Her hair was styled in great swooping whirls. Her dress was a hoop-skirt wrapped in black netting and festooned with dozens of tiny houses, cars and other stormy ephemera.

A friend of mine (whose whereabouts since the hurricanes I was unsure of until I saw her on Christmas Eve) explained that it’s generally accepted that people in New Orleans will burst spontaneously into tears during even the most cursory conversations.

“Any little thing will trigger it,” she said. “I mean you say hello and you’ll get sobs. But everyone knows to just be quiet for a minute and it’ll pass.” Then she added with that cheerful, attractive insolence so common to New Orleanians. “I add 15 minutes of “cryin’ time” to everything. Goin’ the grocery store takes forever. There are more tears than in Tolstoy.”

Like my wife’s dress this line got a laugh. It had to.

It’s glad/sad time down here. Glad you’re alive. Sad about everything else. If you can’t laugh about it, baby you are toast.

There’s been some controversy about having Mardi Gras this year. That it is somehow inappropriate given the scale of the recent tragedy and disaster.

The punch line to that misguided sentiment is that Mardi Gras is a celebration actually devoted to being inappropriate in a community that has courted disaster since the day it was founded.

You don’t build a city on land that sits below sea level and is surrounded by water and not expect to get soggy at some point. It is a geographical crap-shoot well understood by New Orleanians and Mardi Gras is part of their gallant disregard for that particular and unpleasant reality.

It’s one of their ways of laughing at doom.

The history of Mardi Gras is so deep, vast and strange, that it’s difficult to encapsulate. Starting hundreds of years ago with the shepherds of Arcadia and detouring through most of the more interesting cities in history it has always been steeped in sin and redemption.

The Romans. The Greeks. The Catholics. They’ve all put in their two bits of paganism or piety.

But it’s fitting somehow that much of Mardi gras pomp and plumage would evolve from the carnivals of Venice, that other impossible city at odds with time and tide.

And for all this historical pedigree there’s still something very childish about Mardi Gras.

If you are exposed to it as a kid you will never be quite like other people. How could you be?

You’ve watched an entire adult population, your parents, your aunts and uncles, your teachers or your school principles; all your authority figures, suddenly transform into Poseidon, or Mae West or a cross-dressing Santa Claus. Everyday life becomes an overnight Technicolor fever dream. Schools close. The daily schedule is thrown out for a new schedule of parties and parades that become an unending delirium where it’s not inconceivable but in fact highly likely that you might look out the den window at any given moment and see several dozen men and women dressed as Yogi Bear drift nonchalantly by in a papier-mâché galleon.

It’s like somebody knocked over the TV set and cartoons came spilling out.

For those of us who grew up in Louisiana, ”The Wizard of Oz” was like a documentary. Dorothy left Kansas and simply went to Mardi Gras.

Talking trees and wicked witches seemed perfectly normal if you’ve seen your librarian walking down St. Charles dressed in a gorilla suit and a set of woman’s breasts complete with blinking neon nipples.

As a result we tend to grow up with a keen sense of life’s absurdity and a healthy regard for the curative potential of fun.

And there is no fun quite like a Mardi Gras parade. Its epic silliness can be very seductive. It is one of the marvels of modern man that the quest for giving or catching cheap plastic beads can lead people of every temperament to engage in behavior that is singularly, perhaps historically ridiculous.

Not that I’m a pillar of normalcy but I do pay taxes and manage to mingle in polite society occasionally, yet I once led an organization, called the Mystik Knights of Mondrians Chicken. In homage to the great painter we rode in a giant cube shaped chicken, wore costumes the color of yolks and threw egg shaped beads, while white helium balloons were periodically released from a hole in the chicken’s ass.

After three years with this same float we were told by the parades organizers that we would have to change our design. The Novelty of our cubist chicken had apparently worn off. It just wasn’t weird enough anymore.

There are people, ordinary both feet on the ground people who, during Mardi Gras sport titles like The Lord of Misrule or the Abbot of Unreason.

It’s all so perfectly foolish. And essential.

It fills some vast human need to, however briefly, be something else, a satyr, a god, or anything deliciously forbidden. You simply don a mask and give in to enchantment, desire or foolhardy joy.

This year’s Mardi Gras will be the most surreal of all. Never has the gaiety confronted so grim a reality. The walls of rubble, the vanished neighborhoods, and the memory of the city from before the storm haunt every street.

But Mardi Gras has had troubled times before. One newspaper wrote in 1851, “The carnival embraced a great multitude and a variety of oddities. But alas! The world grows everyday more practical, less sportive and imaginative. Mardi Gras with its laughter-moving tomfooleries must content itself with the sneering hard realities of the present age.”

The streets of the city are in black and white now. Like Dorothy’s Kansas. A thin coat of grayish dust covers entire neighborhoods since the flood.

Maybe this will make the traditional green, purple and gold colors shine out even brighter.

New Orleans is a “let’s face the music and dance” town. It always has been. Try as they might, the sneering hard realities cannot keep it down.

But it’ll be harder to catch the beads this year. Those spontaneous tears will make it tough to see.

William Joyce

No comments:

Post a Comment